When a neutron beam meets a sample, neutrons ricochet away from the material in various directions in a process called “neutron scattering.” The scattered neutrons interact with specialized detectors that enable mapping of the particles’ speed and trajectory to deduce where atoms of interest are and how they’re behaving.

This information allows researchers to determine the structure and properties of materials by studying them in various forms such as liquids, powders, and crystal samples. Insights from these studies can inform the production of better batteries, development of more effective medications, and other practical applications. Because neutron scattering experiments would not be possible without neutron detectors, a team at the Department of Energy’s (DOE’s) Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL) develops them in-house for each instrument at the lab’s Spallation Neutron Source (SNS) and High Flux Isotope Reactor (HFIR).

“Think of the detectors as the eyes of an instrument,” said Rick Riedel, an ORNL senior research scientist who has worked on detectors for over 15 years. “They help you see where and when neutrons scatter. From that information, you can tell what is going on inside a crystal.”

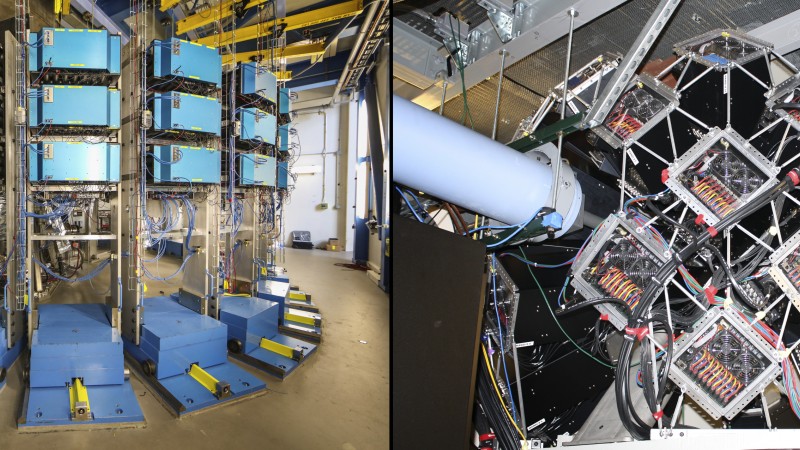

Many neutron detectors are made using helium-3, a gas that has many desirable properties and has been in use for more than 50 years. However, other materials are needed to meet the increasingly demanding requirements of neutron scattering instruments. Anger cameras and wavelength-shifting fiber (WLS) detectors are two technologies in use at SNS that make use of these different resources.

Both Anger cameras and WLS detectors can be categorized as scintillator-based neutron detectors. These scintillators are sensitive enough to detect single neutrons. Scintillators absorb the scattered neutrons and emit flashes of light to indicate the final position of each particle. (Outside of neutron sources, scintillators serve as radiation detectors in airports and as medical imaging devices for diagnostic purposes.)

Riedel and his team design variations of scintillators and other detectors based on the scientific specialties and physical constraints of instruments to provide the best possible data during experiments.

“The design for each instrument is specifically tailored to optimize the data we can collect from real samples in the beamline,” Riedel said.

The ORNL development team won an R&D 100 award for the WLS detectors and another for the helium-3 Pharos neutron detector system. They continuously work to improve upon the original detector designs, often by combining existing technology with more modern resources.

“Anger camera technology has been around since 1970, and we made use of modern electronics to improve the resolution and reliability of those detectors,” Riedel said. “We are currently developing a new generation of Anger cameras that will be even better.”

They also monitor emerging technologies around the world that could potentially be incorporated into future designs. Riedel considers international collaboration with other scientists and facilities integral to the continuous cycle of detector development.

“It’s a constant push to develop and install better and better detectors,” he said. “We could be enabling new science when we design detectors with higher resolutions or lower levels of background noise.”

The team tests new detectors for key factors like rate, resolution, and uniformity in a detector lab and at a HFIR development beamline, then runs simulations to ensure they work properly before beginning the installation process. They also facilitate ongoing instrument upgrades by modifying existing detectors and adding next-generation models that capture neutron data from as many angles as possible.

“Filling out the detector suite increases the amount of data you can collect in a shorter amount of time and generally improves the user experience,” Riedel said. “It’s really exciting to improve the operation of an instrument this way.”

One instrument that received this treatment is MaNDi, SNS beamline 11B, which Riedel describes as “a soccer ball of Anger cameras.” More recently, the team upgraded half of POWGEN, SNS beamline 11A, by adding 10 new WLS detectors.

In addition to these upgrades, other planned projects include developing improved scintillators, producing new detectors for high-resolution neutron imaging instruments, and designing fast detectors for future instruments with higher data rates.

“Most of these projects are in the pre-production stage at this point,” Riedel said. “As we continue to produce high-quality detectors, we know novel discoveries could be just around the corner.”

SNS and HFIR are DOE Office of Science User Facilities. UT-Battelle manages ORNL for DOE’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit https://science.energy.gov.—by Elizabeth Rosenthal